Every year, the non-graduating members of band and orchestra play Pomp and Circumstance and the national anthem at graduation, but it seems that this tradition will not apply this year. If that’s the case, I’m a bit glad that I won’t have to hear the people who play out of tune. There’s more of them this year than there were in previous years, and the absence of seniors to play among them at graduation would make their atrocious intonation even more apparent. That’s beside the point, though. I appreciate the efforts of those who want to improve, and I definitely want to see my non-graduating orchestra friends at graduation; I want to walk on stage and throw my cap in the air with my classmates and take pictures with friends. None of that will happen on our scheduled graduation date. Much to our dismay, everything will take place virtually, a move that other educational institutions have made with their own graduations and other events.

That includes Admitted Students Day and college visits. Yesterday I attended my committed college’s Diversity Program. Exclusively for accepted students from underrepresented racial, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds, the Diversity Program is usually an all-expenses-paid visit that lasts three days. This year, due to the pandemic, it only lasted several hours and was hosted through Zoom, leaving me exhausted.

This came as no surprise to me, as I’d been in countless Zoom meetings prior to this one. When the quarantine started, I thought that Zoom meetings would not be enough to fulfill my extroverted needs. But when tiredness overcame me after an hour-long video chat with a friend, I began to question my extroversion. I was supposed to feel energized, not tired. Was this really the threshold of social interaction for me? Not long afterwards, I began seeing posts about Zoom fatigue on social media and the news, and I realized I wasn’t alone. To my extroversion, Zoom fatigue is a paradox: it is both insufficient and excessive. Zoom still does not satisfy my need for socialization, yet it is more draining than in-person interaction with people. And as the school year ends, with virtual events approaching quickly, I anticipate the feeling will accompany me more and more. Whereas in previous years, when I felt invigorated after talking and hugging seniors and taking pictures with them at their graduations, my graduation will only impart exhaustion in me.

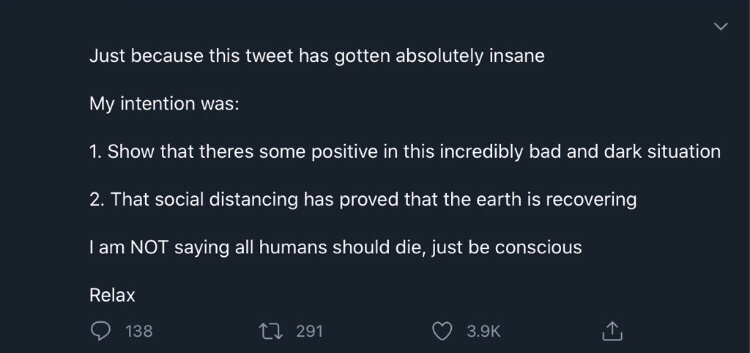

Thinking about Zoom fatigue lends itself to thinking about the broader subject of all types of social interaction via technology—a distressing subject to think about. Even with Zoom meetings, the already prominent role of text messages, emails, and group chats has also increased. This has led to some interesting thoughts in the autistic self-advocate community. A while back, I found an Instagram post that argued maybe the quarantine will make people realize technology-based socialization is valid, and that people should stop giving others a hard time for not wanting face-to-face interaction. The post brings up a particularly distressing conflict for me because in several ways, I do find face-to-face interaction somewhat demanding. I can’t always make eye contact comfortably as an autistic person. Even when the person is fine with my lack of eye contact, not making it feels a bit jarring. Sometimes I have a monotone voice that some people like to point out. With my slow mental processing speed, I’m better at writing than I am at speaking, as I need to take time to organize my thoughts.

Even then, my need for in-person socialization trumps all. Having to rely on messages so much makes me want to throw my devices out at times, but I stop myself; I know I need them more than ever if I want some kind of interaction, because the face-to-face type just isn’t possible outside of family without sacrificing public health. So I imagine that the consequences of the quarantine might turn out to be more complicated than the post proposes. People may start recognizing the value that virtual communication has for many individuals, yet at the same time, they might come out of the quarantine valuing in-person communication more than ever, having been deprived of it.

I don’t mean to discount the needs of the people who are more inclined towards texting and/or Zoom meetings. Indeed, if you’re one of those people, I advise you to take my words with a grain of salt or stop reading so that this post will not burden you. If I’m interacting with someone who prefers that over face-to-face communication due to sensory overload, arguing against their needs is selfish. Additionally, all institutions should take the time to think about how to make themselves accessible to disabled and neurodiverse people, pandemic or no pandemic.

Yet on a more personal level, I’ve become more afraid—and lonelier too. I feel as if I don’t fit in with the autistic self-advocate community. Of course, every autistic person’s different. There’s a popular saying: “If you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person.” But in the autistic circles I’m in, it seems that most of them enjoy the aspect of social distance. I’m one of the few who don’t. I have also realized that during this time, more people have started to understand their preference for digital communication. Before the pandemic, I’d worry that if I asked someone to hang out or talk, they wouldn’t want to. Thus, I didn’t ask. Now that I’m getting tired of virtual communication, I’m terrified that in the future, if I ask someone to hang out or talk in person, they will want to text instead. On the outside, I’ll say, “Oh, that’s okay,” because they’re not obligated to cater to me, but on the inside, I won’t know how to handle the rejection and break down. So I won’t ask, and instead I remain frozen with anxiety, waiting for someone to reach out to me.

![First photo: “Oh my God, I’m gonna cry! My senior activities!” Second photo: “Kim, there’s people that are dying [of coronavirus].”](https://baconnatedchurro.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/34e2486c-9992-4a21-8009-ac402ff038f3.jpg?w=750)